“Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.”

— Bible, New Testament, Galacians 6:7

The system of cairns appeared out of nowhere in the middle of nowhere, with no discernible connection to anywhere else, as though they had been planted by a disoriented Johnny Cairnseed before last autumn’s record rainfall. This did not seem like prime cairn country and I could not for the life of me comprehend what inspired the guilty party to start schlepping rocks to pile atop one another in hopes of establishing a more-formalized route in a place that, since I began traipsing around these parts well nigh 38 years ago, has remained wonderfully wild, or at least wonderfully wild feeling. There were so many cairns, and they were so big, that it took me several visits in order to restore this lovely area to its natural condition. My civic duty sufficiently completed, I opted to wander around a bit atop a path-less and, now-cairn-less, mesa so beautiful and rugged it alone would be reason enough to call the beautiful and rugged place where I hang my hat home.

After an hour or so of pleasant destination-free zigzagging, my peripheral vision latched onto an out-of-place object stuck in the branches of a mature alligator juniper tree that was growing sideways out of a small cliff face. It was bright blue and about the size of a football. To access it, it would take a bit of the kind of effort that, in this, the ancestral homeland of Geronimo and his tough-as-nails Chiricahua Apache brethren, often results in scrapes, contusions and bruises to both the physiology and the ego. I limbo’d under a blown-down ponderosa pine with a wide array of protruding, pack-grabbing branch stubs. I shuffled over boulders that were strategically placed in such a way as to dissuade advance. I slalomed through a sea of fully mature agaves. I busted my way through outward-facing juniper branches that did not seem even slightly inclined to yield any sort of right-of-way. And, with floral remnants in my hair and minor wounds decorating my exposed shins and testifying to my focused stupidity, I finally arrived at the out-of-place object, which turned out to be, of all perplexing and incongruous things, a cylindrical, one-gallon Rubbermaid water cooler.

Now, how this cooler came to be resting in a tree branch way out here in the glorious back of beyond, I could not guess. Given the challenging access of its resting place, I deduced that it must have been tossed out the window of an airplane that had been passing overhead, which seemed highly unlikely on several levels, given that, from a cursory examination, the cooler looked to be structurally uncompromised. Whenever something appears out of place in Gila Country, one normally concludes that the forces of raging floodwaters have come bear. But, given the geomorphology of the proximate terrain, such a causal link would have defied the foundational laws of physics.

I held the polymer-based mystery in my hands, perplexed. I shook it gingerly and could hear and feel that it held loosely packed contents of some unknown sort. Then it dawned on me: Numerous times in a backcountry career that has spanned more than a few years and miles, I have come across supply caches left by hunters or survivalists or long-distance backpackers or folks who envisioned some future circumstance when and where they might find themselves in need of surreptitiously placed supplies, a la Seldom Seen Smith in “The Monkey Wrench Gang” when he was on the run from the law. It is an operational axiom of backcountry travel that is simultaneously unwritten and writ in stone that one does not disturb another’s cache. But this inexplicable vessel did not seem substantial enough to actually be a cache, at least in the traditional sense.

Perhaps it held the ashes of a passed-away compadre, a backpacking amigo or a beloved dog.

Perhaps it contained hidden drug money!

Or, better yet, hidden drugs!

Perhaps it contained a treasure map!

Or a bomb!

Or a bombshell!

Curiosity getting the better of me, I slowly unscrewed the top and found within the container a small notebook and several miscellaneous items: two cheap ballpoint pens, a couple books of matches, some buttons, a Mardi Gras bead necklace, some pennies, two spent CO2 cartridges and a few Band-Aids. The contents did not exactly lend illumination to the enigma I now held in my hands. Then I examined the notebook and only then came to realize that what I possessed was in fact something I had only ever heard about but had never witnessed in the flesh: a geocache. Give all the possibilities that had just seconds prior been swirling around in my head, this was a disappointment in the extreme.

For those of you who may not be acquainted with this form of outdoor-recreation, geocaching is game wherein participants place items that boast little in the way of monetary value — such as CDs, pages torn from comic books, gum-wrappers, postcards, whatever — within waterproof repositories — such as military ammunition boxes, Tupperware containers or bright blue gallon-sized Rubbermaid water coolers — which are subsequently hidden somewhere out in the boondocks. Descriptions, directions and/or actual GPS coordinates to the site are then posted on the various geocaching websites. Those inclined to participate in such a vacuous activity proceed to attempt to locate the geocache they are seeking. If they succeed, they sign the logbook that all geocaches contain, place an item in the cache, perhaps remove an item that will eventually find a new home in some geocache up the road (this is apparently called “hitchhiking”) and, I guess, scratch their nuts and pop a celebratory, self-congratulatory cerveza.

Though geocaching can trace its roots back to a 150-year-old game called “letterboxing,” which evolved (where else?) in the British Isles, it was birthed only in the year 2000, when the U.S. military released its stranglehold on the kind of detailed GPS technology we all now take for granted as we are trying to navigate our way along highways and trails by relying upon an electronic device rather than relying upon our own senses.

The first geocache was placed in Oregon in 2000 by a man named Dave Ulmer, who now apparently holds Yoda-like status in the geocaching world. Since the first cache — which contained software, books, a little money, videos, food and a slingshot stashed in a half-buried plastic bucket — was established, logged and located, geocaching has expanded and spread like a particularly virulent case of crab lice. It has morphed to include numerous variations, such as virtual caches, geodashing and stratocaching, the latter of which actually involves airflight (making my original thesis regarding the Rubbermaid water cooler I now possess being dropped from a plane seem more plausible).

As well, numerous groups, such as geocaching.com, opencaching.us, Groundspeak and the Geological Society of America, have jumped into the geocaching game. There are locationless, webcam, Chirp, Wherigo and reverse caches. There is a geocaching-specific line of gear and clothing. There is a “Geocacher’s Creed” (more on this later). There have been deaths associated with attempts to find geocaches. There have been instances when bomb squads have been called when a geocache has been found in a public place. Various legislative and regulatory entities have addressed geocaching by passing laws prohibiting the placement of caches in public parks and in cemeteries.

It will surprise no one that, when geocaching first hit the outdoor media shortly after that first cache was placed in Oregon in 2000, I rolled my eyes. The late-’90s and early-aughts seemed like an especially ripe time for concocted forms of outdoor recreation.

In short chronological order, we had the birth of:

• Highpointing — the goal of achieving the high points within the boundaries of some artificial political or administrative construct, like Rocky Mountain National Park, a county or, in the case of the State Highpointers, the entire country.

• Orienting — a thankfully short-lived activity wherein participants would attempt to precisely follow a given compass bearing no matter what obstacles or environmentally fragile areas (and here I think mainly of cryptobiotic enclaves) might come between bullshit manufactured point-A and bullshit manufactured point-B.

• Creeking — another short-lived activity wherein adherents would follow a creek from mouth to source. The goal was to stay entirely within the creek — and here I mean actual boots or sandals in the water — the entire time. I have no personal experience with this particular scientific demographic, but when creekers were padding about with frigid tootsies, apoplectic limnologists were emerging en masse from wherever it is they normally hang out to vociferously condemn creeking, creekers and anyone who might have ever known a creeker. The furor regarding the potential negative environmental ramifications of creeking resulted in this “sport” dying an ignominious, and justified, death.

If forced to speculate a decade ago, I would have guessed that geocaching would have been a fast-passing trend, more like orienting and creeking than highpointing, which shows no signs of fading away.

I would have guessed wrong.

According to geocaching.com, the self-proclaimed “official global GPS cache hunt site,” there are now almost 2.4 million registered geocaches spread throughout the world, and as many as six million people scurrying around seeking those caches out.

And, I would learn in short order, there are, stunningly, a serious shitload of geocaches located in areas where I regularly tromp.

Which, at this point, is neither here nor there, because, right now, I am faced with something of a minor-league moral quandary: I am standing way back in the Gila National Forest holding what amounts to a piece of trash that was left in a place where trash ought not be left. Ordinarily, I would, without hesitation, tote that trash with me as I made my way back to civilization, where it would be unceremoniously tossed into an appropriate receptacle, a no-nonsense process that would likely be accompanied by an invective or two hurled toward whatever nameless person or persons it was who left the offending piece of rubbish in a tree branch back in the woods. But I did not. I returned the Rubbermaid water cooler to its perch. I suspected I would soon come back to take some remedial action, but in the meantime, I had some research to do. As well as some cogitation.

When I got home, I immediately began scouring the Internet for pertinent skinny relating to geocaching, an online hunting trip that eventually yielded most of the data presented in this screed. More than that, though, I much desired to try to hunt down the specific origins of the geocache I had just found. It was surprisingly easy to do.

On the geocaching.com website, I learned that the bright-blue plastic Rubbermaid one-gallon water cooler was placed in 2001 by two fellow Silver City residents I do not know (or at least I do not think I do), who I’m sure are very nice, sincere, well-meaning people. The geocache even had a proper name, which for obvious reasons I will not herein share. The website contained a fairly detailed set of directions, along with some GPS coordinates, along with what looked to be a code cipher of a species usually associated with a Cold War passing of national secrets. Here is an example: ybbx sbe n pnvea bs ebpx ba gur yrsg naq tb gb nabgure pnvea bs ebpx ng. Ordinarily, I would think such seeming gibberish would be a computer glitch or a mistake of some easily explainable sort. But the other geocache websites I visited contained similar cryptic letters.

The description of the geocache I had stumbled upon included a total of 42 logged visits from people who had attempted to locate the Rubbermaid water cooler. About half of the people had located the geocache and about half had not. The last person to have successfully located the bright-blue water cooler had done so scant days before I found it.

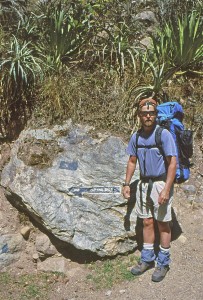

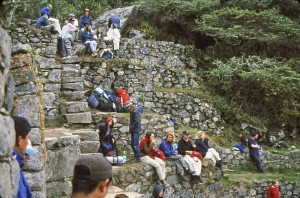

There was also a gallery of photos of people who had succeeded in their quest. Everyone pictured looked like the kinds of folks I either drink with, hike with or regularly run into while I’m out and about on the trails of Gila Country. That is to say: Not as young as they used to be. Rattily attired, with nary a stitch of current Patagonia or The Northface attire procured from REI. Beat-up daypacks. Scuffed boots. One guy was sitting smoking a cigarette. Another guy was drinking a can of Budweiser. Superficially: Kindred spirits.

All told, I’m sitting there in front of the flickering computer screen thinking, “What the fuck, these people seem OK.” Ergo: What they are doing out in the woods by extension must be OK too. What’s wrong with me?

But one big thing caught my attention most while I was eyeballing the website: The geocache I had found was not where it had been originally placed! Its original home was under a rock overhang I have visited on numerous occasions. Someone had moved it a half-mile or so to the juniper branch I had chanced upon. Thus, I concluded, someone else had experienced the same moral quandary I was now facing. Or perhaps moving a geocache, but not moving it far, is some sort of geocaching humor. Or maybe there are antagonistic relationships between the various geocachers operating in the same area.

Either way, I clearly needed to revisit that bright-blue Rubbermaid one-gallon water cooler, where my choices would be: to return it to its rightful place under the rock overhang, to leave it where it lay in the juniper branch or to carry it out of the woods.

Since some bonehead had removed the aforementioned system of cairns, it took me longer than I would have expected to re-locate this wayward geocache. After a languid hour of meandering to and fro, I came to think that whoever had moved it from the rock overhang to the tree branch had come back to finish the job. But, eventually, its bright blueness became visible through the dense brush.

I had not formulated any sort of criteria upon which I would base my eventual decision regarding the geocache’s immediate fate. Perhaps if I just sat and held the Rubbermaid water cooler for a few minutes, some sort of heavy-duty message would percolate though its insulated shell and travel through my fingers and arms all the way up to my brainstem. Maybe the very land upon which I trod would speak to me and direct my mentally muddled self to the morally correct course of action. Maybe I should just smoke some hash and see if I even remembered why I was where I was.

When I first interfaced with this unattractive urn, I had paid only cursory attention to the words scribbled in the notebook it contained by people who were successful in their geocaching quest. This go-round, I opted to scrutinize those words carefully, in hopes that, by so doing, appropriate action would be forthcoming.

There were a total of 72 entries over the course of 13-plus years, with many of those entries covering more than one visitor. Since the space allotted for “remarks” was small, there were not many of the kinds of loquacious ruminations often found in registers located atop mountain summits. (Thank goodness for small favors.)

Here are a few of the entries:

• Just found out about geocaching yesterday, so this is my first find. Great fun, easy directions, beautiful location. Took deck of cards.

• Just came by for a second visit to this cache. On my way for a day of exploring the area.

• Visiting from California. Out for an adventure. Great fun!

• Tried to find this past May — unsuccessful. Great hike. Really used our GPS. Thanks.

• Tough hike. No trail for us. Had fun. Great adventure.

• I like it here. Totally quiet.

• Very hot. Forgot the water. Found plenty of cactus. How do we get out of here?

• I was here as a child and now as a child again.

• Took Buddha (for luck). Left baseball cap.

• Must have taken the hardest route to cache!

• Take a right where?

• What an ordeal!

OK, now how can anyone be so haughty as to find anything wrong with those entries, with the people who penned those entries or with the inspiration and impetus that brought those people to this undeniably special place?

There is no doubt that I tend to glance askance at contrived reasons for venturing forth into the great outdoors. When someone opts to unicycle to the top of a Colorado Fourteener, or when someone tries to set the record for running up and down Mount Elbert, or when someone uses one of those stupid goddamned devices that keeps track of how many vertical feet you ski in a day, I find myself rolling my eyes, shaking my head and wondering what the fuck ever happened to just walking through the woods light and unfettered. This is not to say that I believe the only acceptable modus operandi for backcountry forays consists primarily of sitting under a tree pondering Thoreau or Muir while searching frantically for deep metaphors regarding the lamentably short lives of caddis flies.

But, well, sometimes contrivedness gets a bit out of hand and, as a result, I feel that the Big Picture — the preservation of the backcountry and the resultant spiritual benefits for visiting the backcountry — are more and more getting lost in a sea of lists and experience-enhancing technology.

But when I have chatted with people about their quest to “bag” the highest peaks in every state or their desire see how many vertical feet they can ski in a day or their attempts to break the speed record to the Appalachian Trail, there will generally be positive-sounding commonalities. They will say things like, “It gives me a good excuse to travel to places I ordinarily would not visit.” Or: “Having attainable goals helps me focus on getting in shape.” Or: “I enjoy being part of a community that shares my passion. I’ve made a lot of good friends while [fill in the blank].”

Again: What could possibly be wrong with any of those perspectives?

Well, personally, I think they stifle the natural, and beneficial, predisposition mankind has toward goal-less wandering. I think they represent a herd mentality. And I think, in the end, that not everyone thinks like me — which, in most circumstances, is a reality I would argue that’s a blessing for both me and the rest of humanity.

Besides, who’s to say that the people who enjoy recording their vertical ski feet or chasing around geocaches do not spend plenty of time sitting under a tree pondering caddis fly lifespans? Judging from the entries in the notebook located within the geocache I found, there seems to be at least as much nature-based contemplation associated with their geocaching exploits as there is with me and my ne’er-do-well muchachos as we make our willy-nilly way across the great wilderness expanses that define our local horizons.

Besides, it’s not like geocachers are dumping plutonium into pristine rivers.

Everyone and their dog could enthusiastically take up geocaching tomorrow, and the resultant negative ramifications would be a bump on a gnat’s ass compared to the environmental disaster that is the downhill ski/resort/real-estate industry. As it is, geocaching ranks well below even the groomed cross-country-ski-area industry when it comes to adverse impacts. It less impactful than even bird-watching.

All things considered, I would certainly rather people take up geocaching than paintball or golf.

Sure, perhaps because of geocaching there are a few more warm bodies traipsing through territory I would much rather have all to myself, but, truth be told, only one time have I ever come across another soul in the area where I found that Rubbermaid geocache. It’s not as though the huddled masses are suddenly eschewing malls and descending into the woods in search of one-gallon water coolers that hold ballpoint pens and Mardi Gras necklaces. And, even if that were the case, it could well be argued that the world would therefore be much better off if such were actually the case. More people would come to love the outdoors. People would be less stressed. People would lose weight. And on and on.

Additionally, it’s my guess that a significant percentage of geocaches are placed in parks in urban Ohio rather than in the relatively untrammeled lands of the West. And, further, it’s my guess that most geocachers live in cities in the East and maybe even in foreign realms. So, again, the number of geocache participants claimed by geocaching.com notwithstanding, it’s highly unlikely that a tsunami of GPS-toters will be descending upon my blissfully unpeopled home turf anytime soon.

Still, I am old enough that I remember when mountain biking did not exist. Then, there were a few hippie-looking dudes pedaling through the backcountry on klunkers. Now, mountain bikers form the dominant trail demographic throughout the nation. I don’t think geocaching will ever approach mountain biking in popularity, mainly because there’s a palpable top end on potential gear sales, but, hey, in a world where more and more people measure skiing acumen via the number of vertical feet they descend in a day, you never know. In my time, I’ve seen some mystifying shit come down the trail. Nothing surprises me any more.

The logical underpinnings of my negative reaction to this one little piece of trash being left unattended out in the Gila National Forest were fast eroding and, consequently, the self-righteousness that is part and parcel of my personality was losing its customary inviolate center.

Then, in near desperation, I started reading some of the fine print in the little notebook that had so recently caused chinks in my sanctimonious psychic armor.

Numerous of the entries had lamented the lack of a trail to the geocache that had originally been placed under that overhang. One of the entrants wrote that he had started clearing a trail. And another wrote that he had started … placing a series of cairns to help people more comfortably access the geocache. Yes, the very system of cairns I had spent so much time returning to their natural state was birthed as a result of this geocache! Here my self-righteous sanctimoniousness regained its solid footing, much like how one recovers during a sparring match in Tae Kwon Do after your opponent has landed a strong but glancing kick to your midsection.

While I get having goals and looking for excuses to visit places you ordinarily wouldn’t, I do not get, and I never will get, the desire to modify the environment through which one passes — especially when that modification transpires in a place that, before your passing, was pretty much off the map. And even more so when that modification will result in more and more people following your footsteps.

We have precious few wild areas left. In my warped little world at least, wild trumps access, and wild trumps use, and it damned sure trumps games. Every time.

Count me among those who argue that we ought have less trails, less trail signs, less detailed maps of wilderness areas and damned sure less GPS coordinates and Google Earth images. Let people wander and get lost and maybe found and maybe not. Let them be surprised by abysses and rivers impossible to cross. I understand we are pretty much stuck with trails, trail signs, detailed maps of wilderness areas, GPS coordinates and Google Earth images for no other reason than those things are institutionalized components of The System.

Geocaching damned sure is not.

Though its worldwide numbers are substantial, relatively speaking, geocachers represent a negligible percentage of those inclined to wander through the woods. But, given the number of geocaches that apparently exist, if even a handful of people seeking those caches out (and there’s one in every bunch) opt to start building illegal and most likely poorly designed access trails and/or cairn systems, the impact could easily become disproportionate on numerous levels. Erstwhile-unvisited fragile areas might start seeing bootprints. Erosion will assuredly increase. Impacts on populations of animals that avoid human contact will increase. And, well, the sense of exploration, faux that it might be in these dark, over-civilized days, that comes hand in hand with wandering through what little trail-less land remains will be further diminished. We need more disorientation, not less.

The Geocacher’s Creed that I alluded to earlier states, among other activity-specific axioms:

• Obtain the best possible coordinates for your cache to reduce unwarranted wear on the area.

• Avoid leaving tracks to the cache.

• Leave the area as you found it or better (e.g. pick up litter).

In my view, a geocache itself is litter. And, if the Geocachers’ Creed unambiguously states that leaving tracks and unwarranted wear on the area is a no-no, then surely the process of building a system of cairns to a cache is a violation that merits the death penalty.

According to geocaching.com, what I then decided to do is considered a crime. Verily, there’s an entire system of geocaches in another part of New Mexico that apparently was recently completely removed by a person or persons unknown. The man who established that system of heisted caches — which numbered more than a dozen — filed a complaint with the Forest Service, which is apparently actually investigating the case. The complainant contends that the geocaches are personal property, even though they are intentionally left unattended and without permit upon public lands. He contends that he ought to be compensated for the value of the geocaches and for the time spent placing those caches.

Well, this is not exactly the first time that I’ve stood proudly at odds with the legal system. That bright-blue Rubbermaid one-gallon water cooler now sits upon my desk, scant inches from where these words are being penned. It will soon be placed into the recycling bin, from where I hope it is resurrected into something useful, or at least benign. Its contents will be placed in my trashcan. And I will soon start eyeballing the appropriate geocaching websites with the idea of expanding my public-service horizons to include as many geocaches as I can locate and remove.

It’s good to have goals.

And this quest will give me an excuse to travel to places I would not otherwise visit.

Not sure I’ll make many friends. But you never know.