The Georgia Street house, 35 years after the fact

The Georgia Street house, 35 years after the fact

“Now I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

Angels watch me through the night,

And wake me with the morning light.”

— “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep,” a much-revised prayer, the earliest form of which was penned by Joseph Addison in 1711

Phase One: Myclonic Jerk

A lingering lower-back problem has mandated in no uncertain terms that I embark upon the tedious process of procuring a new mattress. My initial investigation into the associated commerce has revealed a stunning spin on economic theory as it relates directly to a personal lifestyle equation that has pretty much been writ in stone for many decades: In order to significantly upgrade my bedding situation, I will have to shell out approximately the same amount of money it would cost me to purchase a round-trip ticket to, well, pretty much anywhere that boasts an international airport.

It’s not as though I now lay me down upon a bed of nails. My current mattress was bought from a store named something like House of Snooze. Maybe not top shelf as far as sleep system retailers go, but neither was it a yard sale taking place behind a crack house. I think the price surpassed triple digits, but not by much. Still, for the past several years, it has been a decided step up from the beds of my sordid past.

Just the other day, I drove by a hovel over on Georgia Street that I occupied in the early 1980s. That it is still standing shocked me, as it was in a state of near decomposition when it was passed down to me by a young lady — an acquaintance of an acquaintance — who was leaving town in order to broaden her vocational horizons. (She was an aspiring prostitute who found the pecuniary potential of dirt-poor Silver City somewhat discouraging.) The hovel consisted of three small, drafty rooms: a sparse kitchen that did not sport so much as a square millimeter of counter space, a bathroom so small that you almost had to sit crossed-legged on the toilet and a combination living room/bedroom.

The budding hooker, who was trying desperately to find a gullible person to relieve her of a lease that was not due to expire for some months, told me the place was furnished. Turns out, the furnishings consisted solely of a three-legged chair and a disintegrating screen door that was mounted on four cinder blocks. The woman considered the latter to be a very versatile — to say nothing of decorative (in an extremely minimalist sort of way) — piece that doubled as both couch and bed.

Since the hovel rented for only $80 a month, I took it. I placed a dissolving three-quarters-length Ensolite sleeping pad I had been given by a Good Samaritan halfway into my thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail atop that screen door and called it good. Basically, after having spent the previous several years sleeping on the ground as much as I slept on a bed, I really didn’t give a shit. I had electricity, heat, indoor plumbing, running water and a roof over my head. That was living large for yours truly in those free-floating days.

My hovel quickly became a gathering place for wayward ne’er-do-wells of all stripes.

One of the regular visitors was a young man I shall herein call Willie. Willie was a half-Native American who hailed from a small town adjacent the Mescalero Apache Reservation. He spoke fluent Tex-Mex and enjoyed making intoxicated merry perhaps a bit too much, as we all did. He was ostensibly a college student who, like many of my cohorts, received a fair amount of financial aid with the idea that, eventually, a graduation would ensue, but who, in actuality, usually finished each semester with three incompletes, a D-minus and a dropped class that never was officially dropped because he had forgotten he ever signed up for it in the first place.

As testament to how low our standards were, I learned one day over bong hits that I was something of a hero to Willie. He told me I was the only person he associated with who actually occasionally went to class and actually finished each academic year with verifiable evidence that I was making progress toward a degree. Given that I was anyone’s definition of a desultory student, I was simultaneously flattered and fearful for my future.

Willie lived a quasi-nomadic life. He couch-surfed. He often slept illegally in the basement of one of the dormitories. He camped. Occasionally — mostly at the beginning of each semester, when he was flush with cash — he would rent a room in a local flophouse.

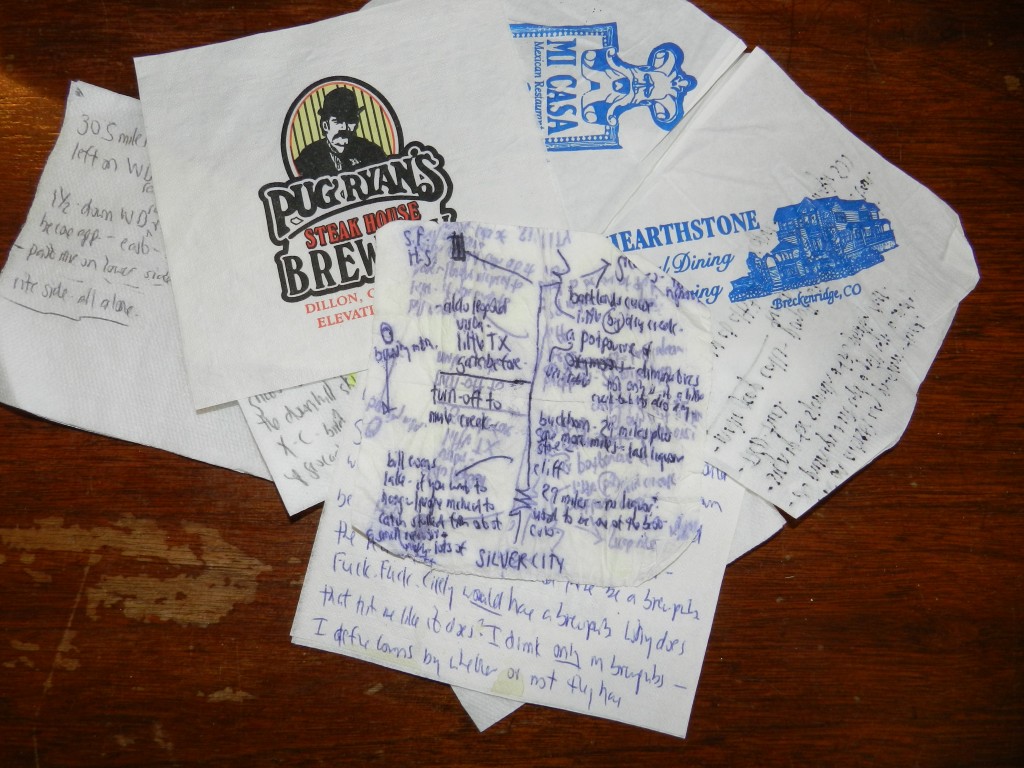

One day, Willie, who had been squatting in an abandoned shack up near Pinos Altos, delivered to me good news. With cold weather coming, he was moving back into town. And the shack had within it an old mattress that, Willie said, was a step up from my Ensolite-adorned screen door. He scratched some rudimentary directions onto the back of a brown grocery bag that had most recently been used to deliver five-pounds of skanky ditch weed to an unscrupulous local dealer who had a well-earned notorious reputation for repackaging inferior smokeables, applying to them inappropriate over-the-top appellation — bullshit stuff like “Gila Red” and “Mimbres Dynamite” — and selling them at grossly inflated prices.

That very evening, I drove my battered putty-colored ex-UPS Ford van — which came my way in an off-the-books transaction that included a 10-speed bicycle, a 12-string guitar, eight grams of sticky black opium and $200 cash — up the rutted road scratched onto Willie’s hand-drawn map. A few miles up the hill and, sure enough, there was a diminutive cinderblock building matching Willie’s verbal description. It was obviously associated with a long-abandoned mining operation. Probably, it was used to store explosives. It was maybe 12 feet by 12 feet and had only a couple very small windows near the roofline. In place of a door was a brightly colored fake Navajo blanket hanging from two nails.

The inside was surprisingly well tended. While hardly spotless, it was clean in a Thoreau/Walden Pond sort of way. There was a broom leaning against a wall. There was a small table and two chairs. There were several candle holders and an oil lamp. The walls were decorated with badly outdated calendars sporting incongruous pictures of snow-covered mountains.

And, in one corner could be found the goal of my quest: a twin-sized mattress. According to Willie, the shack in which the mattress was located was, much like the dump I called home, bequeathed from resident to resident and had been for many years. Remote and hidden as it was, the only way anyone would learn of its existence was to be told by someone who likely planned to move on. This marked the third time Willie had lived in the shack. Thus, he knew the mattress was an integral part of the residence. This knowledge led to a multi-tiered mental wrestling match on my part.

First, I felt a bit bad about horking a resident fixture from the domicile.

Second, I recoiled a bit when I considered the biological back-story of the mattress. A visual reconnoiter did nothing to assuage my concerns regarding the mosaic of stains that covered both sides. There were unidentifiable discolorations mixed with mysterious blotches interspersed with inexplicable smudges commingling with bewildering blemishes. Basically it looked like a biker-gang-related crime scene that had transpired in a Third World meatpacking plant. It’s fair to say the DNA was highly contaminated.

Yet I was not dissuaded by my uncharacteristic revulsion. Though, given its soiled condition, the mattress was much heavier than I expected, I wrestled it singlehandedly into my van and proceeded directly to my slum, happy as a pig in slop.

Phase Two: Slow Wave

Willie’s relationship with that mattress did not end with my run to the old mining shack he had lately called home.

Willie was what I would have to call a combination of background music and wallpaper. He was often there … at a party, at a cookout, when students gathered in the arroyo next to the Eckles Hall dormitory to get high. He rarely contributed anything besides his presence, which was pleasant in an unoffending sort of way. If he had drugs, which was not often, he would share them enthusiastically. Mostly though he was one of those people you didn’t notice was gone till he came back. He would add comments to a conversation but rarely commence discourse. He was physically unobtrusive, maybe five-five, 120 tops. He had deep brown eyes and high cheekbones rising above a badly pockmarked face. He wore a faded serape that looked like it was inherited from Clovis-era ancestors, and he wore it with dignity. His straight, shoulder-length jet-black hair was parted in the middle. He wore a bright-red bandanna around his head. He would have been a perfect subject for an Edwin Curtis photogravure.

Willie seemed like an orphan who made you want to foster him but not adopt him.

Just before Christmas break, three pretty, and pretty wild, women dropped by my Georgia Street hovel for a few days. I had met one of the ladies the previous summer. She had been working as a volunteer ranger at Badlands National Park up in South Dakota when I passed through on my way from Georgia to British Columbia. We hit it off. She and her two traveling companions, all from New York City, were navigating a behemoth drive-away stationwagon to Southern California and, since Silver City was less than an hour off Interstate 10, they detoured so the ranger lady and I might reconnect.

With two unattached vixens in town, friends came out of the woodwork, giving the women a choice of local male material as we planned various daytrips into the Gila National Forest, one of which was a hike to Turkey Creek Hot Springs, one of the most magically beauteous destinations in the entire Mountain Time Zone.

Vixen number-two invited a sorta buddy of mine, who I later learned practiced grand larceny as a sideline. He had lent me a brand-new IBM Selectric typewriter, which was the same kind of machine used by none other than Hunter S. Thompson! The grand larcenist said, since he had graduated, it was gathering dust in a closet and he knew I would put it to good use. At the time, I was working off an old manual Underwood I scored at a local pawnshop for $40, so the thought of upgrading to what was then the apex of typing technology was very appealing. Months later, while cleaning the electric typewriter, I turned it over and there on the bottom was a metal label describing it as property of Western New Mexico University. It had been heisted and I was therefore indirectly complicit in a felony perpetrated upon my alma mater.

I suppose the typewriter thief was using me — and who knows how many other people? — to store his ill-gotten goods until such time as he deemed it safe to fence them. Under cover of darkness, I carried the typewriter, along with an anonymous note explaining the situation, to the campus security office, where I left it on the front step.

When next I ran into my felonious friend, I told him I had some bad news: Someone had entered my abode, which was left perpetually unlocked, and made off with the Selectric he had so graciously lent me.

“Well, I think you should pay me for my loss,” he replied lamely.

“First, I need to file a police report,” I said. “As the actual owner, you’ll probably have to fill out some forms.”

The subject was never again broached.

But I did not know about my chum’s dark side as we were planning our foray to Turkey Creek.

The third woman invited Willie, who might have been taking advantage of the fact that she was breathlessly enamored of all things indigenous by embellishing his noble-savage bonafides. (Hell, for all I knew, maybe he was — as he intimated to the impressionable damsel — a direct descendent of both Geronimo and Cochise.) Willie was so stunned, he could scarcely stammer out an enthusiastic affirmative.

So, six of us piled into the behemoth stationwagon, which, according to the drive-away contract, was not to be used for any sort of extracurricular activities and furthermore was really most sincerely not to be taken on unpaved roads, and proceeded to navigate it for a solid hour down a track that was numerous operational levels beneath the description of “unpaved.”

We crossed the Gila River twice with that stationwagon, a decision that caused a certain amount of consternation on the part of the three women whose names were etched upon the drive-away contract. I assured them all would be well. This promise I made despite an applicable experience to the contrary. A scant year prior, with me serving as obstacle spotter while sitting on the hood of an old Datsun sedan, my associates and I got stuck up past the wheel wells while crossing this exact same stretch of the Gila and had to wait till the next morning for help while the car sat in the middle of a flow that rose with each passing hour. A four-wheel-drive pickup truck eventually came by and got itself stuck helping us, which necessitated waiting several more hours for another four-wheel-drive pickup to happen by and, with all three vehicles spinning tires, grinding gears and maxing out their tachometers, we managed by the skin of our teeth to get safely to high ground.

But these three ladies from New York City did not need to hear that. So, with yours truly at the wheel of a vehicle I had no vested interest in preserving, I recklessly gunned it across the Gila without issue, or at least without issue that concerned me.

It’s a solid 90-minute hike to Turkey Creek Hot Springs, two hours if you are ingesting handfuls of drugs, which the typewriter thief, Willie and I were doing with reckless abandon. The women not only did not partake, but they were all haughtily repulsed by what pretty much everyone I associated with in those days took as a behavioral given.

Oh, well.

The typewriter thief was standoffish during the entire experience. He was a refugee from the suburbs whose only interest in this outing took the form of the lady who had invited him. He was intimidated by the New Mexico wild.

Willie, on the other hand, was having the time of his life. Not only was he in a stunning locale he had never before visited with people whose company he was enjoying immensely, but he had for once in his life been purposefully included on the guest list. And by a buxom beauty who, as she effused on numerous occasions, found him to be one of the sweetest men she had ever met. She seemingly wanted to begin the process of bearing Willie’s children as soon as it was convenient for him to whip his noodle out.

Few things in the world trump contributing to someone else’s well-deserved happiness.

We enjoyed some skinny-dipping in the hot springs, followed by a nice picnic lunch the ladies had prepared. I wandered upstream a few hundred yards to doze in the late-autumn sun. Though the creek was noisy enough that it served as an acoustic buffer, some verbal commotion interrupted my reverie. At first, I thought it was just my compadres messing around. As my attention focused, however, I could hear my name being called in a tone and at a volume that clearly indicated all was not well, that the cosmos had just taken a big nasty ol’ shit right in the middle of a here-and-now that, scant seconds prior, had been downright agreeable on all levels. My friends were flat the fuck freaking out. Hands were raised above heads like a combination of a Southern Baptist revival and a chainsaw-based horror movie. People were running willy-nilly and bumping into each other. Sandwiches were flying every which way. I dashed back and there lying on the ground was Willie in the midst of the worst grand mal seizure I have to this day ever seen. The dude looked like he had been plugged into a 240-volt electric socket at the same time he had been possessed by a particularly malevolent demon. He was jerking so badly that, even with my full body weight attempting to restrain him, he continued to flail wildly.

Foam spewed forth from his mouth like an unattended high-pressure firehouse running amok and his eyes were rolled back so far we could not see his irises, much less his pupils. Various important body parts, like, as but one random example, his head, kept banging into proximate boulders. Blood mixed with sand.

This situation was the denotation of “buzzkill.”

The three women were far too busy screaming and running into each other and dropping sandwiches to be of much assistance. And the typewriter thief just stood there, hands limply at his sides, looking lost and forlorn.

My spontaneous plan was to minimize the thrashing-based physiological damage and to try to talk Willie back to our particular skewed version of reality. Eventually he returned. He was dazed and disoriented in the extreme. He wanted to know why I was lying on his chest and why I was telling him everything would be OK in a voice unambiguously suggesting I had to earthly belief anything would ever again be even remotely OK.

This situation was exacerbated by the sobering realization that we had before us a hike across rugged terrain, punctuated with many sketchy creek crossings. Willie was wobbly. He needed two of us at his side to make any forward progress. He stumbled often and this sweet kid was fast turning seriously belligerent to the point of combativeness. He simply could not understand what was going on. He had no recollection of his seizure and argued that we were making it up just to embarrass him. One by one, the women fell away exhausted and distraught, and the typewriter thief walked ahead as fast as his pitiful excuse for legs would carry him. I believe I even saw him flapping his arms trying to fly away.

So, for much of the hike out, it was just Willie and I.

It took us four hours to reach the waist-deep Gila River, which we had to cross on foot to reach the stationwagon. The whole way, Willie fought me. I had to resort to every variation on the cajoling theme I could mentally muster. I encouraged him. I related stories of our various partying escapades. I lied through my teeth by telling him how much fun we would have with those three women once we got back to town. I called him a fucking pussy and disparaged every bad-ass Native American stereotype I could think of. None of it worked individually. All of it worked in the aggregate.

When we finally and thank-godfully made it back to the behemoth stationwagon, we put the seatback down and laid out Willie — who was then, like all of us, soaked from the river crossing. The three women gathered around and took turns talking encouragingly, while the typewriter thief stared glumly out the window. There was little else to do on the first-aid front during those pre-cell phone days

With the last tendrils of dusk hovering above canyon walls almost 4,000 feet deep, I inched that old stationwagon across the Gila, knowing full well that the last thing we needed was to get stuck in the middle of the river. I then drove a bit faster than prudence normally would have dictated down the rutted and serpentine dirt road that would eventually connect us with pavement outside the village of Gila, from where I redlined the car, which, by then, was sporting a few more unidentifiable rattles than it had before our trip commenced 10 hours prior.

Topping out at 100, we made it back to Silver City in less than half an hour. My goal was the emergency room of our local hospital, a long-since-demolished haunted-house-looking facility that had as much a reputation for inexplicable death as it did for restoration of health and well being. First, though, the indignant typewriter thief demanded I take him home. He had been muttering for several hours about how he could not believe what a fucked-up outing he had signed on for and how he would never under any circumstances even consider joining us for another foray, no matter how many unattached lasses we could offer as company. I told him I would drop him off at a street corner that would necessitate him walking maybe 15 blocks. He harrumphed and egressed the stationwagon without saying good-bye or even closing the door.

We were greeted promptly at the emergency entrance by two attendants, one of whom placed Willie, who was by this point bouncing between quiet detachment, overt discombobulation and profanity-laced belligerence, in a wheelchair, and one of whom transcribed my recollection of events. There were numerous questions to both Willie and I regarding types and amounts of illegal intoxicants recently ingested. I was slightly embarrassed that I could not recollect exact pharmacology and specific dosages.

“Many and much” was the best I could do.

When he was asked if had ever experienced a seizure before, Willie mumbled, “I fell down once when I was young.”

The three women returned to my Georgia Street residence. They sped away at first light.

I sat exhausted in the waiting room. Several hours later, a young male doctor came out and reported to me that they had performed several tests, which showed, yes, Willie had indeed suffered a grand mal seizure. The doctor could tell I was spent. He put a hand on my shoulder and said, in all likelihood, Willie would fully recover, but they wanted to keep him for a couple days just to be on the safe side

The doctor then whispered: “You did all the right things under the circumstances. There’s not much else you could have done. He’s lucky to have a friend like you.”

I went to Willie’s room to see how he was doing. He was heavily sedated. He looked comfortable lying, maybe for the first time in his life, on a plush mattress on clean sheets in a sterile roomful of beeping and blinking monitors with an IV bag hanging next to him and a clear hose running to his exposed forearm.

I went back to the hospital two days later. Though there was little more they could do, the doctor was reluctant to release Willie, since he apparently had no home address and no one to look after him.

“He can stay at my place till he gets better,” I heard myself saying.

Willie rested on that same disgusting mattress for the better part of a week. His nocturnal agitation was so intense, I slept out in the backyard. One morning, when I went inside, he was gone. No note. No Nothing. Just gone.

I did not see Willie for several months. As buds began appearing on the elms lining the streets of Silver City’s historic district, he stopped by out of the blue, not quite acting as though nothing had transpired that day along Turkey Creek, but almost. We smoked a joint he brought with him, talked about upcoming final examinations — which I would be halfheartedly taking and he, once again, would be missing. A few other friends came and went, but Willie extended his visit, apparently purposefully.

“Do you ever hear from those women?” he asked, casually, once we were alone.

“Nah. Seemed like that ship sailed.”

“Sorry I fell down that day,” he said, staring stoically straight ahead.

“You feeling better?”

“I don’t know.”

There was an awkward silence.

“When I woke up and you were holding me down and calling my name, I thought you were an angel,” Willie said. “Your head was glowing and you had wings.”

I couldn’t for the life of me figure how he made me out to be a member in good stead of the heavenly host. Maybe the sun was at my back, illuminating my unkempt locks. And maybe two of our cohorts were standing behind me in such a way that their bodies appeared to a man lying on his back emerging incrementally from a seizure as feathery appendages.

Either way, it marked the first time in my devilish existence I had ever been mistaken for a divine being.

After another long silence, Willie asked: “That mattress still working out?”

“Yes it is,” I said. “I appreciate you pointing me toward it.”

And, with those few allusive sentences, we both understood my mattress-based debt to Willie had been paid in full, with interest duly accrued.

I spent the summer working as a night watchman on a paddle-wheeler on the Mississippi River. Midway through the next fall semester, I realized I had not seen Willie since I returned from the humid hell of the Big Muddy. No one seemed to know what had become of him. To this day, I have heard nary a syllable about his whereabouts or his condition.

Phase Three: Paradoxical

That nasty mattress stayed with me for several years. It alternated between the floor of the various slums I called home and the back of my battered van. It was while taking refuge in that van that it absorbed additional stains.

There was a post-midterm Bacchanal scheduled for the Middle Box of the Gila River, just downriver from where I extricated Willie from his seizure nightmare. I drove to the correct coordinates and spent an appropriate number of hours engaging in academic discourse with people whose tongues were lolling out of their mouths. Somewhere between dusk and dawn, I decided it was time to part ways with my fellow revelers, most of whom, like me, were too hammered to articulate proper valedictions.

One person who was face-planted into the sand bordering the river was an amigo I’ll call Hawk, who was, even by New Mexico’s forgiving cultural barometer, a strange hombre. He was, first of all, 20 years the senior of most every student at our local college. He had opted to return to the classroom with a grey beard and arthritic hands bent into perpetual claws partially because he was tired of living a bottom-feeder hippie lifestyle and partially because he, a Vietnam veteran, qualified for generous financial aid. And, because he had a young son, he was also given a subsidized on-campus apartment, which he shared with an extended tribe of fellow Rainbow Family members, most of whom were named Moonbeam, Cinnamon and Dancing Bear.

Hawk was a talented and passionate writer who I employed to work for me at the student newspaper, which I edited for three years. We became friends, though I have to admit his omnipresent philosophical eccentricity often negatively impacted my attempts to seduce some of the coeds who then traveled on the periphery of my social trapezoid.

Hawk maintained a working still in the back of his apartment. The still was actually owned and operated by a crusty old hard-rock miner I’ll call Cactus Jack. Cactus Jack, who passed away several weeks after being thrown from a highway overpass by someone who was never identified, much less brought to justice, was an in-your-face barroom evangelist who downed boilermakers at the Drifter Lounge in between rambling tabletop invocations. He also taught me how to pan for gold, a skill I managed over the years to parlay into numerous paid writing assignments, including the first piece I ever sold to Backpacker magazine, where I ended up working as a contributing editor for more than a decade.

Hawk drank Cactus Jack’s homemade moonshine like he was trying to drown something dark. This often resulted in a loss of not only coherency but also consciousness. Which was clearly the case as the post-midterm gathering at the Middle Box was embering its way toward dissipation. Though I suspected I would later grow to regret it, I dragged Hawk back to my van by one leg and leveraged his dazed carcass onto the mattress. I tried to impart some salient information — stuff like who I was and where I was taking him — but all he could do was snore, drool and yak, adding extra layers of DNA to my already-repulsive rack.

Halfway home, I had to stop to take a leak. I pulled over near Saddle Rock, exited the van and relieved myself. As I was doing so, I shouted back, asking Hawk if he was OK. I heard a groan that sounded more or less affirmative in nature, which, in my mind, meant he was still alive, if not exactly kicking.

Twenty miles later, I parked in front of his apartment and walked around to help my sloshed chum inside, only to observe that, where I expected Hawk to be, he was not. This was more of a concern than it might have been in ordinary circumstances, since my van did not have any doors. There was no driver-side door. There was no passenger-side door. Where there were normally two side doors, there were no doors. Where there once had been two back doors, there were no doors. I had removed all six doors because they, being rusted through and ready to fall off anyhow, rattled loudly and that noise bothered me. While a lack of doors did not exactly improve the overall safety coefficient of the vehicle, it sufficiently addressed the noise issue while simultaneously providing a 360-degree vista.

Admittedly, I was not thinking all that clearly, but, still, I was able to mentally muster a plausible explanation regarding my missing muchacho: He had obviously fallen out of my van somewhere between Saddle Rock and where I now stood bumfuzzled. There was of course only one option: I had to drive back to initiate a salvage run for whatever might be left of Hawk.

I pointed my van west on U.S. Highway 180, entertaining while I did so the myriad potential negative possibilities I was facing.

First, there was a good chance I would not locate Hawk, at least until daybreak. If he had indeed rolled out the back of the van, he likely had careened off the road into the brush.

Still, it was possible he had thudded down in the middle of the blacktop, upon which case he would likely have been run over, maybe several times. While the thought of Hawk with tire tracks across his chest made me wince, those thoughts eventually wandered to potential interfaces with the judicial system. What was my culpability? Was I to blame for whatever harm might have befallen my buddy, inadvertent as my actions might have been?

What if I rounded a bend and there was an ambulance and a gaggle of sheriff’s cars, lights a-blazing, while a team of paramedics attempted to revive a moonshine-breathed man whose last words were “John Fayhee.” I myself was inebriated. My driver’s license was both long lost and long expired. I had no insurance. Because I had acquired my van under extra-legal circumstances, I had no vehicle registration.

I could be in deep mierda.

This indeed presented an ethical conundrum.

I mean, I liked Hawk just fine, but not enough to go to prison for him, especially if he was already expired.

By the time all these thoughts were bouncing around in my head like pinballs on speed, I rounded a bend and there on the shoulder was Hawk, upright, but staggering badly, headed in exactly the wrong direction. I pulled over and asked if he wanted a ride.

“Why did you leave me?” he slurred pitifully.

“I figured you needed the exercise,” I responded with faux nonchalance camouflaging a degree of relief that almost had me in tears. It was all I could do to refrain from hugging Hawk there on the side of the highway.

Ended up that, when I yelled after his well being while I was urinating, he attained something approximating functional coherency, and, as I was returning to my position as pilot of my pitiful excuse for transportation, he simultaneously got out to relieve himself. He said he was quite startled to see me drive off.

“I was pissing as fast as I could!” he exclaimed. “You should be more patient!”

True, that.

I helped him back on the mattress and took him home without further mishap.

That mattress and I parted ways when I abandoned a primitive camp way out in the desert. The mattress had been placed on the ground next to a big juniper, where I slept night after night under the stars with a dog and a cat — who added to the stain milieu by bearing four kittens upon it. When monsoon season hit full force, I was backpacking in the Gila Wilderness and the mattress got soaked beyond salvation. I left it beneath the tree, where its remnants might still lie.

As for the van, which by then hardly ran: When I moved to Colorado in 1982, I handed the keys to a man I hardly knew. I took a bus north, to begin life anew in a place where climatic reality required doors.

Phase Four: Rapid Eye Movement

Last week, with mattress-based thoughts swirling in my head, I decided to try to hunt that old shack down, the homey little place from which, with Willie’s directions, I had liberated that funky mattress. The dirt road now has a formal, though prosaic, name: Radio Tower Road — which, not surprisingly, accesses the summit of two peaks that are thick with various species of antennae, dishes, discs and, in all likelihood, electronic surveillance apparatus owned and operated by Homeland Security, which maintains a noticeable, some would say obtrusive, un-Constitutional presence in the borderland area.

When I sought that well-used mattress all those years ago, few people traveled up this road. The mining operations, the remnants of which are visible from the highway connecting Silver City with Pinos Altos, had long been abandoned and, in those delightfully primitive days, the peaks were clear of electronics. Thus, there was no reason to maintain the road. Few people drove up there. Now, with the texting needs of thousands of people depending upon the upkeep of those antennae, dishes and discs, Radio Tower Road is frequently graded and therefore is smooth enough to accommodate passenger vehicles.

I parked at the bottom and, with my dog, set out on foot, opting to combine a stroll down memory lane with some exercise.

With rain clouds forming thickly overhead, we took off toward the summit of the mountain with the most antennae. The road contoured along the face of the ridge, passing into and out of numerous side drainages.

Ahead, in the middle of some of the various mine-tailing piles, I visually acquired my target. Because of the serpentine nature of the road, it took a half-hour to get there, and, when I did, the shack was nowhere to be seen. It was either hidden by trees, or perhaps I had seen something that, from a distance, was a mirage. I continued on toward the summit, but was stopped cold with a no-nonsense no trespassing sign and a locked gate.

On the way back down, I walked more slowly, examining the lay of the land, which was dominated by trash — the bane of rural New Mexico. There was plenty of simple litter: fast-food packaging, beer and soda cans and broken glass. There were uncountable of shell casings, as this, like many areas in the sunny Southwest, is utilized with enthusiasm by people opting to bear arms without opting to clean up after themselves.

There was also a stunning amount of household refuse dumped off the side of the road. Entire truckloads of discarded appliances and furniture filled otherwise scenic side canyons. Intertwined in that refuse were several mattresses. I stood there, raindrops pattering off my hat, wondering about the stories those mattresses might tell. Few household items can trump mattresses for narrative resonance. Dreams. Lovemaking. Going to bed mad. Illness. Scared toddlers looking for parental comfort. Abandonment. Disconsolation. Fretfulness. Prayer. Death.

All reduced to garbage.

I exited the road and entered into one of the dead zones defined by deserted mining operations. While there is much to admire about the place such enterprises hold in the mythology of the Wild West — ingenuity, toughness, vision — the truth of the matter is that most long disused mine sites are ecological disasters with half-lives measured in centuries. I always tiptoe across their toxic soil with trepidation, as though the host of poisons contained therein might seep through the soles of my boots like radioactive Ebola. I breathe less deeply. I wince when viewing the unnatural coloration that defines the polluted pallet of abandoned mines.

Right in the middle of a sea of crumbled cinder was the shack. It had seen some hard times since my last visit. One side was riddled with pockmarks left by point-blank weapons discharge. It looked like the wall of a firing squad facility. There was no colorful Navajo blanket. No candles. No table and chair. No calendars. The inside was a disgusting muddy mess, with what I guessed to be uninspired occult designs on the walls. Dark sullen dankness defined the ambiance. The thought that this place was once used as a domicile, even by people with nowhere else to hang their hat, was impossible to fathom. The thought that I once pilfered a mattress from these dreary confines made my skin crawl at the same time it made me smile.

Like many people knocking with gnarled fists upon the door of their sixth decade, I find myself wistfully mentally wandering back to days when I did not have more parts that hurt than parts that do not hurt. When my back was straight and fully able to solo wrestle a mattress from a shack into the back of a doorless van. When I crashed on whatever came between me and the cold, hard ground.

Phase Five: Awakening

Concurrent with the decision to buy a new mattress is the question of what we will do with the mattress that now serves as the setting for my slumber. I have spent more time directly connected to that mattress than I have any other piece of furniture I own. Certainly, it does not have the historic cachet of my desk, which was once owned by a famous personality. It does not have the coolness of our oak dining room table or our Victorian couch.

Still — upon that mattress, I have pulled the covers around my chin on many a rainy morning. I have taken multitudinous afternoon naps. I have played hand-under-the-blanket with our purring cat for hours on end. Upon its folds, I have dreamed of crossing mountain ridges that defied the laws of gravity. I have dreamed of sailing to Greenland through cold seas with waves as high as the moon. Upon its folds, I have lied awake at 3 a.m. attempting to fabricate a suitable denouement for a nearly finished essay. I have tossed and turned over missed deadlines. I have passed out drunk upon its glorious ridges and folds more times than I care to count. Upon it I writhed for almost three weeks when infected with the H1N1 flu virus. It is upon that mattress that my wife and I consoled each other the night we had to put our old dog down. And it was upon that mattress that I lay prostrate for a week, knocked woozy by painkillers, when I hurt my back three days before we were scheduled to leave on a trip to Cuba.

With all mattresses, there is yin and there is yang. Most of us come in on a mattress and most of us will go out on one, too.

I suspect we will take that mattress to the Habitat for Humanity Re-Store on the other side of town. We recycle the detritus of our almost embarrassingly middle-class life there fairly frequently. Last time, it was two badly outdated light fixtures placed in our house by the people who built it during the Summer of Love. Before I even passed onto the Re-Store property, a woman probably 70 years old who pulled up behind me effused about how lovely those butt-ugly fixtures were. She offered me $5 on the spot. I told her she was welcome to them and she acted the same way I did when I scored that mattress from the shack that now pockmarked with bullet holes.

One person’s trash is indeed another person’s treasure.

The mattress we will soon discard will make a good bed for someone. I hope it will see long-remembered bedtime stories and giggly slumber parties and passionate lovemaking. I hope it will provide comfort when the flu visits and on the day when the old dog is sent over the rainbow bridge. I hope it becomes a snug bastion in an unpredictable world, a world where sometimes you get a surprise invite to join three buxom lasses on a trip to a beautiful hot spring and sometimes you get left on the side of a lonesome highway while taking a piss under the deep dark New Mexico sky.