Part One

“Oh god forgive my mind when I come home.”

— Brandi Carlile, “Wherever Is Your Heart I Call Home”

It was dead smack in the temporal epicenter of yet another of my many not-exactly-making-any-positive-headway periods. I was once again simultaneously treading water and spinning wheels — a resident in good stead of inertia-based cliché city — when I found myself working as slave labor for under-the-table peanuts at a fading-glory marina located upon the muddy and misty shores of one of the many lazy estuaries lining the Chesapeake Bay. I was an unskilled odd-jobs specialist whose duties consisted primarily of painting long-neglected exterior walls that suffered continual impact from the sultry saltwater air. I removed more mold and rot than I applied new paint, though, occasionally, when no one was looking, I’d slather big gobs of bright liquid color onto the ongoing, ever-present decomposition. Occasionally, when things got busy dockside — mainly on weekends — I would be asked to lend a hand with procedures relating to the orderly ingress and egress of watercraft often being steered by people boasting a comical combination of insouciance, ineptitude and intoxication.

Though some slips were occasionally occupied by folks who were living enviable variations on the lean sailor-bum theme, by and large, the marina’s customers predictably consisted of well-nourished folks of more-than-adequate means. The oft-ostentatious manifestations of that affluence — which bore telling names like “Profit Motive,” “Just Desserts” and “Golden Parachute”— were plus-or-minus equally divided between vessels powered by wind and by internal combustion. Either way, the boat owners were generally a convivial lot, insofar as they were not opposed to inviting unkempt members of the working class aboard for a happy hour cocktail or two. Certainly, that hospitality would not have extended to having an unwashed soul such as myself marrying into their clan, but sharing a casual evening beverage with the hoi polloi seemed culturally acceptable. Which, in my limited experience dealing with the upper fiscal crust, amounted to a downright enlightened attitude. For the most part, these were people who may have been spared the guillotine had violent civic upheaval rained down upon their floating plutocratic parade.

There were certainly exceptions. Sometimes, these exceptions were macro in nature, in that they could cover entire finger-snapping crews — from captains on down to deckhands — of boats appropriately christened “Gauche Nouveau Riche Douchebag,” or some such, which had fetched our humble port.

Sometimes, those exceptions were more micro, in that only a single member of a ship’s complement would make the notion of fomenting immediate class-based revolution seem appealing, despite the undeniable negative fiscal ramifications such action would consequently trickle down upon those of us who drove battered vans with dangling fenders and who dwelled in rundown trailers way out in the mosquito-infested fringes of this squishy-moist land and whose watercraft options consisted of semi-rotted wooden canoes liberated from the local Boy Scout troop, of which I was once a member in good stead.

One especially stifling mid-July Friday late afternoon, I was summoned to lend a hand dockside. I sealed my half-empty gallon can, placed my brush upon its top and, with crimson trim paint dripping from my fingers and splattered upon my locks and my ragged attire — making me look like a cross between an ax murderer and roadkill — I walked down into the unpredictable, though sometimes amusing, realm of upscale maritime sociology.

An undeniable advantage of working at a marina — and the main reason I agreed to help out, though it was close to quitting time — was, while most customers were dwelling happily in their golden years, it was not unusual for passenger manifests to include nubile, comely and scantily clad lasses of prime breeding age. Daughters and granddaughters usually, but sometimes friends of the family and sometimes with no discernible blood relation to anyone onboard. (Questions regarding verifiable taxonomy in those instances were rarely posed, at least in the bright light of day.) Whenever a new boat pulled in, there was a veritable elbow-swinging, “Road Warrior”-like death race among the male marina workers to get first flirtation dibs should an unattached babe disembark.

Such was the case this go-round. She was maybe 18, going on 25, petite, buxom, shapely, tanned, minimally attired and a doe-eyed dirty blonde. It did not take long for all the raging testosterone in attendance to come to the sobering and disconcerting conclusion she was toxicity incarnate. Every pore upon her smooth skin oozed arrogant entitlement. She bitched about the heat and humidity. She griped about the lack of shade. She moaned because not a single one of the proximate workers had thought to release the mooring lines in their hands to bring her an unbidden cold beverage. She sneered. She rolled her eyes. She growled. She raised her nose skyward. She was a one-woman malevolent low-pressure system who brought with her the undeniable potential for thunderstorms and maybe even a deadly hurricane.

Her clearly mortified parents sported facial expressions bespeaking a barely suppressed desire to toss their hideous spawn overboard at the next deep-sea opportunity. Yet they did not attempt to intercede in any way. They seemed exasperated, powerless and relieved their offspring was spewing her venomous insolence outward rather than toward them.

As we were still going about basic docking procedures, the boat that unfortunately carried the horrid young lady across roiling waters to our midst — about a 40-foot impeccably clean and tidy bright white fiberglass motor yacht — was drawing the attention of the sizeable resident seagull population, which was always ready to pounce upon a neglected food item. The gulls circled and squawked and a few brazen individuals even lighted upon the stern. The attention of one particular gull, however, seemed focused upon the horrid young lady whose dissatisfaction with everything and everybody within earshot was fast reaching stentorian fever pitch.

The gull flew back and forth several times, losing a bit of altitude with each passing swoop. Then, with a degree of targeting exactitude that would be the envy of every Top Gun pilot ever to don Navy blue, this seagull loosed a full load of shit directly atop the young lady’s head.

In those days, almost every Caucasian female on the planet under the age of 30 wore shoulder-length hair parted front-to-back exactly down the middle. This young lady subscribed wholeheartedly to that unimaginative fashion template. A professional cake decorator wielding a precision frosting nib could not have lined the seagull shit out anymore perfectly along the exact center of this lady’s razor-straight hair part.

And I am not talking about a light load of shit. It was as though the seagull had breakfasted upon a double order of green-chile-infused huevos con chorizo. This was one huge pile of seagull shit. And it landed with an audible splat impactful enough that the young lady winced a bit when it hit. She, of course, had no earthly idea what manner of foulness had soiled her crown.

She instinctively lifted her hand to investigate. Unfortunately for her, the hand came down open palmed with a bit more force than the situation merited. Had this seagull excrement taken a more traditional solid, or even semi-solid, turd form, perhaps her instinctive action would have resulted in fewer negative consequences. As it was, the pile had little in the way of molecular integrity. Think a consistency of dysentery-infused guacamole. Nasty shit. She reacted like she was swatting a horsefly that had bitten a big chunk out of her scalp. The resultant multi-vectored trajectory of the seagull shit was reminiscent of a child jumping into a mud puddle. The entire top of her head became adorned with fecal mousse. She was essentially sporting a defecation yarmulke.

Yet she still did not know what had transpired. It was not until her mitt came down to face level that the grim situational truth hit home via a combination of intense visual and olfactory input. Her pretty face instantaneously contorted into a grim, horror-movie caricature of itself. It was reminiscent of those over-the-top Photo Booth selfies that distort one’s mug till it looks like it’s melting on the computer screen. She momentarily froze, her visage bespeaking an attitude that said, “This kind of thing does not happen to me, especially in front of a slew of plebian strangers.”

Lamentably for this now-literally-odious female, the incident unfolded in front of a rather large audience, whose attention had been focused for some minutes on the girl because of her obnoxiously boisterous attitude (well, that and her undeniable attributes). The reaction was not even slightly sympathetic. No one stepped forth to volunteer to de-shit her locks. There were barely stifled guffaws from people occupying nearby boats. Close-at-hand fishermen and crabbers chortled and pointed and howled things like, “In all my years, I’ve never seen a seagull shit right on someone’s head!!!!” Even the girl’s parents had snot streamers spurting great distances from their nostrils. The marina employees were lying prostrate on the dock choking with sidesplitting laughter.

The young lady, already dealing with tresses overflowing with the foulest form of excreta imaginable, found herself the subject of overt ridicule as the words “seagull,” “shit” and “head” spread like wildfire from the core of the marina to the restaurant/bar, to the swimming pool, clear out to the facility’s chain-linked periphery, where people took their pets to relieve themselves. Folks who had not witnessed the event ran from distant realms in hopes of catching a glimpse of the shit-headed teenager, who was currently in the throes of apoplectic convulsions.

The crowd was increasing by the minute. That someone did not think to quickly erect an admission kiosk to sell tickets to view the amazing shit-headed teenager was surprising.

Throughout what was quickly becoming a chaotic circus-like atmosphere, I was the lone person who stood frozen and expressionless, a limp bowline still in my possession. My gobsmacked amazement overwhelmed my motor reflexes.

My gaze kept moving from the girl’s shit-covered head to the seagull, back to the girl’s head, back to the seagull, which was cackling victoriously as it continued to circle above, just out of reach. Others saw the shit hit the vixen’s head, but no one else had seen the buildup, how the gull had flown back and forth, sizing up its target not once, not twice, but three times, before opening its anal bomb bay doors and discharging its sizeable payload.

There could only have been three possible explanations for this unlikely occurrence, all of which shared a common degree of overt, undeniable implausibility.

1) It might have been a case of pure happenstance, one requiring an uninterrupted line of highly unlikely compounding component coincidences stretching clear back to when some sub-sentient Pleistocene slime creature farted, effecting a butterfly’s wing flap, which itself caused a pinball cascade through time immemorial clear up to the point where that big load of shit hit the girl’s head. This possibility I did not consider likely.

2) Maybe there was actual premeditation on the part of the seagull, an animal with a brain the size of a pea. Yes, perhaps this winged creature hatched and executed a deliciously devious plan of attack upon the young lady’s cranium because, like the humans standing on the dock, the seagull was irritated by her unpleasant demeanor. I also considered this scenario highly unlikely, though there is no denying a seagull’s penchant for participating in behavior easily classified as seemingly intentionally irritating.

3) Or perhaps there were greater forces at play. Cosmological-level forces. In order for the offending gull to accurately lay a massive load of mucilaginous caca upon the noggin of the young lady, there, somewhere in the great unknown beyond, had to exist a supernatural drone pilot joyously manipulating a joystick wired to the seagull’s onboard navigation systems.

I was stunned to realize the most logical conclusion was the least logical, the most supernatural. I mean, six billion years of planetary cohesion is not near long enough to account for the fortuity necessary for the load of seagull shit to have serendipitously hit the girl on the head at the exact crescendo of her opera of obnoxiousness. And anyone who has spent any time around the coast knows seagulls are far too stupid to concoct any plan more sophisticated than “nab unattended piece of rancid fish bait from the boat railing.”

Ergo: For the first and only time in my life, I felt there might actually be an almighty celestial entity, one with the kind of sense of humor that would look down upon a creaky wooden dock in a rural Virginia hamlet and notice a young lady who karmically deserved to have a shockingly voluminous load of seagull shit deposited atop her head. Then to do it, to steer a seagull with sufficiently laden bowels to the right point in time and space, with an itchy though patient finger on the eject button, thinking “not yet … not yet … not yet … NOW!!!” That’s the kind of sky daddy I could grow to appreciate and maybe even worship. Way more so than the kind inclined to smote cities and turn people into salt pillars simply because they were curious.

I found myself in the disorienting position of being on the verge of metaphysical metamorphosis.

Before I could cogitate further upon the potential quantum implications associated with this shit-based event, my stream of consciousness was rudely interrupted by a terrifying screech. The young lady was rapidly descending into full freak-out mode. Her orbs bulged. Her entire body started to quiver. It was like she had been possessed and was in sudden need of an emergency exorcism. Had her head spun completely around while spewing vile bile, I would not have been surprised in the least. Suddenly, without warning, or at least action-specific warning, the damsel-in-distress took off at a dead sprint. Her goal appeared to be the safety and privacy of her family’s large boat. In her temporary, shit-stained rage, her aim was understandably askew. Rather than finding refuge in familiar environs, she almost immediately lost her balance and tumbled off the dock. This was not a graceful entrance into the aquatic environment. It was an ass-over-teakettle, limbs flailing, face-first flop, which only served to exacerbate the guffaws, chortles and side-splitting laughter.

The tide being low, the water was only about five feet deep, which meant the girl — who I’m certain is to this day stricken with a paralyzing combination of ornithophobia and scatophobia — could, once she achieved physical equilibrium, stand upright with her face high and dry, but not by much. She was, however, a psychic mess. Though her less-than-graceful interface with the briny drink had dissolved much of the seagull shit, she was still weeping and pulling at her hair as though her now-sodden locks were on fire. Her pitiable circumstance raised the spectators’ amusement factor even more. Tears were rolling down people’s faces. There was life-threatening hyperventilation. Even her parents were bent over, almost puking with hysterics.

The situation was no longer funny.

I climbed down a barnacle-covered ladder and slowly moved toward the disconsolate teenager, who seemed more helpless little girl than potential sexual quarry. I spoke calmly and tried to soothe her. She stopped blubbering long enough to look my way. I thought she was starting to chill, to maybe even realize her situation, however embarrassing, was really no big deal. However, as I approached, her eyes saucer-sized and she screamed so loudly there were acoustic ripples on the surface of the otherwise glassy water.

“What the fucking fuck?” I growled exasperatedly.

“SHARK!!!” she shrieked, while pointing at me. She began backstroking with extreme avidity.

Only then did I look down and realize the water immediately surrounding me was bloody. Intensely so. I heard “Oh shit!” spring from my mouth as I began reflexively thrashing.

All laughter stopped and all jaws dropped, for it was instantly assumed by those there gathered that, given the undeniable bright-red aspect of water, what was going on was no longer a kind-hearted, albeit disheveled, marina employee helping to soothe a young lady who was humiliated on several levels, but, rather, some sort of noteworthy subsurface carnivore action. When you live in a coastal area, you hear stories — apocryphal on a good day — about how, when people are attacked by a shark, the bite can be so clean the victim — forevermore known as “Stumpy” — does not realize he or she has been attacked until he or she reaches down to grope for an appendage no longer there. I had never heard of any shark sightings hereabouts, but it’s not like there was a fence between the marina and the open ocean to keep them out. With great trepidation, I began to explore my lower extremities.

It was me who was now hyperventilating. For, you see, one of the reasons I never became a true ocean person, despite spending my formative years close to the Atlantic, was, somewhere along the line, I developed a not-entirely-irrational fear of sharks. I don’t know for certain the movie “Jaws” was responsible, but it certainly aided and abetted the discomfort I felt — and continue to feel — toward every member of the superorder Selachimorpha. To this day, I rarely enter salt water without keeping a steel eye peeled for dorsal fins.

And here I was, standing in a murky estuary listening to a mad woman who lately had her head shit upon by a passing seagull yelling “SHARK!!!” at the top of her lungs.

At that exact moment, the owner of the marina — a greasy little tyrant detested by everyone who knew him — walked around the corner and, oblivious to recent events, froze dead in his tracks. A ream of papers tucked under one of his flaccid, stubby little arms fell onto the dock, subsequently to be borne by the wind into the river. What he saw was two people flailing about in blood-red water — one of whom was still yelling “SHARK!!!” and one of whom — me — was flapping his arms so violently, it looked like he was trying to achieve flight at the same time he was exclaiming “oh shit oh shit oh shit ” while a captive audience surveyed the scene with a combination of stunned dismay and scarcely disguised amusement. He raised a nubby digit, pointed to my general quadrant, lips moving though no discernible words forthcoming, spun half a turn and fainted, hitting dock like a sack of spuds. For all anyone knew, he had just died of a heart attack. Under normal circumstances, that would have been cause for folks to respond in some manner, since he owned the marina where all this was going on. Given the choice of watching a long-haired weirdo getting devoured by a shark, while a bikini-clad, shit-headed vixen backstroked in the opposite direction at 30 knots or administering CPR to a greasy little tyrant, well, that was no contest.

By the time I completed my underwater assessment of my body parts, all of which seemed present and accounted for, the young lady was about halfway to Spain. At last, I came to a happy realization: The redness of the water was not caused by any sort of shark attack, but, rather, by the paint coating my entire vocational life seeping off my clothing, hands and hair into the water.

“It’s OK,” I shouted with considerable relief, “it’s only paint!”

Everyone groaned in obvious disappointment and began to disperse. The young lady’s parents, who were still having trouble reengaging their respiratory systems, like their reaction to their daughter’s adversity had been building up since the nanosecond she popped out of the womb, finally regained their authoritative equilibrium and demanded in no uncertain terms that she knock off this theatrical nonsense and return post haste to terra firma. She was last seen receiving a ration of finger-wagging grief for “making such a scene and embarrassing us all,” while being led firmly by the shoulder to the confines of her family’s boat, still pulling nervously at her hair. From inside the cabin, I could hear yelling, though I could not make out what was being said.

I ascended the barnacle-covered stairs and parked on a nearby bench to gather what few wits I yet retained, while my fellow marina employees desultorily helped the marina owner, who, though badly bumfuzzled, was, sadly, not dead, to his feet. Once he was more-or-less oriented, he realized all his important papers were heading out to sea. “A week’s work lost,” he lamented. “Maybe they could be saved,” he halfheartedly hinted to one of the dock boys, who, once he realized the man who signed his paychecks was on the road to recovery, snickered and walked away. The sleazy marina owner stumbled back to his own boat, a 70-foot ornate schooner that boasted a life-sized, hand-carved, naked, voluptuous mermaid on the bowsprit.

Cocktail hour had kicked in and all around the sounds of affable, alcohol-infused chitchat could be heard above the squawks of the seagull flocks.

Part Two

“I want all the women

all the money

and all the fun

I want every rainbow

all the marbles

and a personalized introduction to God

I want a death list

transparent skin

and a cat with no fur

I want everything

I have nothing

I will negotiate”

— klipschutz, “america”

Since it was well past the end of the workday, I could have driven my battered van with dangling fenders to my rundown trailer way out in the mosquito-infested fringes of this squishy-moist land. Instead, I opted to fetch my semi-rotted wooden canoe — 14 feet long with enough remaining flecks I could tell it was once long ago a lustrous shade of blue — and paddle out into the muggy dusk as hydrous haze rose from the surface of the tepid water. I often enjoyed silently slaloming my lonesome way between the grandiose watercraft moored in the river.

There is no doubt I did so with pangs of envy, which is an embarrassing thing to admit.

As previously indicated, this period was not the highlight of my life. I had moved back to my home county after two years living in New Mexico because of a woman, who, shortly after my ill-advised return to the land of ticks and chiggers, summarily dumped my ass — for good cause, I might add, which did not exactly make the unceremonious and mortifyingly public parting any easier to absorb. As well, those few of my amigos who still dwelled in that sweltering place had recently been en masse busted as part of an undercover DEA sting that netted an impressive array of heroin, LSD and pot. With court dates looming, they were rationally laying very low on the fun-and-frolic front, which meant I did not even have anyone to party with. I was adrift — emotionally and spiritually — in the metaphoric doldrums. Going nowhere slow. And, by a long shot, I did not have the fiscal wherewithal to temper, much less rectify, my woeful circumstances.

It would have been one thing had there been any lofty philosophical overlay guiding, or at least rationalizing, my insolvent circumstances, which operated like a feedback loop on top of a perpetual motion machine on top of a flushing toilet. There were not. I had taken no vows of poverty. I had not become a recent convert to Thoreauvian simplicity. I was nothing more than a disorganized, unmotivated, uninspired fuck-up, and it was starting to piss me off clear down to my DNA.

I paddled close enough to those well-appointed boats I could reach out and touch them. Touch them I always did, the same way I came to regularly do with trees later in life, like I was hoping perhaps I would be on the receiving end of some osmosis-based wisdom or enlightenment or some energy or maybe a stock market tip I could take advantage of with zero in the way of upfront investment. I knew full well there was likely much to abhor about the back stories of the people whose names were printed upon the titles of these vessels, each of which was costly beyond my ability to calculate. Though, as I said, most of these people were hospitable enough, at least superficially, there was little doubt many of them had filled their personal coffers by means that would make even a laxly oriented moral compass spin crazily. Some were retired military contractors who laughed about war. Some were fatted refugees from the world of arbitrage, where entire industries were bought, sold and bartered for the appraised value of their sum components, consequences to employees and towns be damned. Some, like the greasy little owner of the marina at which I toiled, simply represented the rectum of capitalism by way of squeezing the life energy out of every individual and entity that crossed their greedy path. There was also no doubt many of these people were, beneath the outward social waterline, bigots, classists, elitists, racists and sexists. However, they undeniably were bigots, classists, elitists, racists and sexists who, on some level, probably many levels, had their shit together.

I wanted to have my shit together. I wanted some perceivable and comprehensible bright flash of insight to shoot out of one of those boats into my fingers and up through my arm and into my heart and into my brain — even if it took the form of the sizzly sparks that fried the fingers of the Wicked Witch of the West when she tried to remove the ruby slippers from the feet of her dead sister as she laid smooshed under Dorothy’s crash-landed abode.

Nothing like that ever happened.

I pointed the bow toward open water illuminated by a waxing gibbous moon.

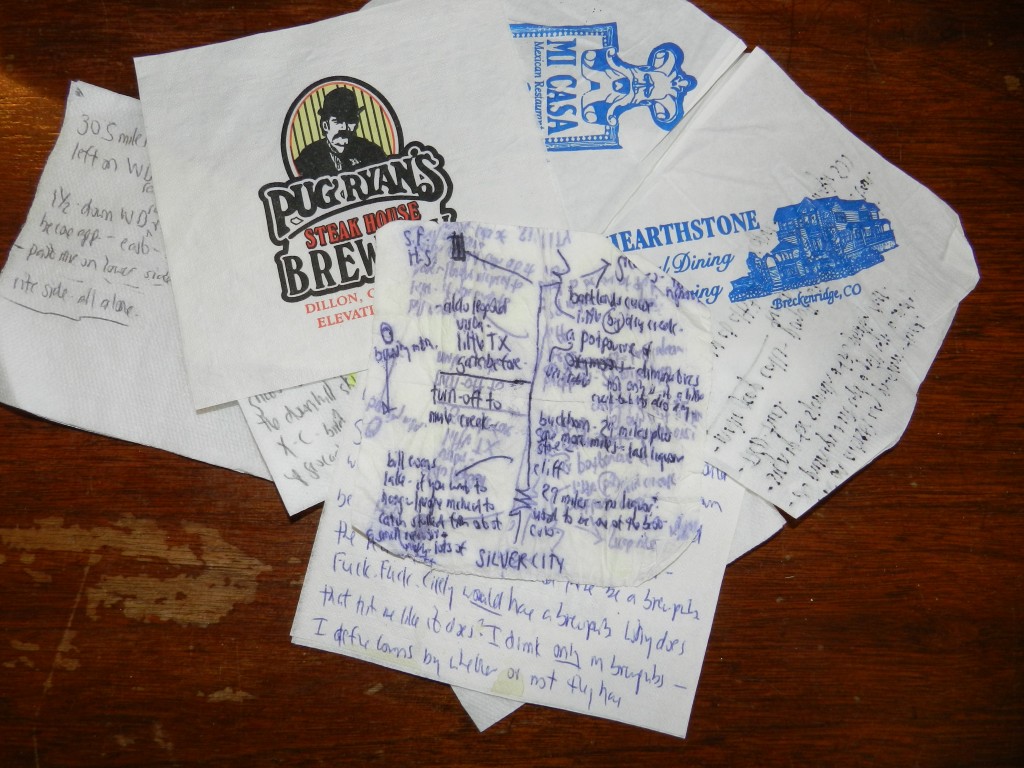

My entire life, I have had an unquiet brain. My thought processes run amuck. I have always had trouble corralling the disjointed whirlpool within my head and, thus, I have always had trouble ordering my near-constant introspection. This has long been an issue that, while sometimes fun at drug-infused parties, does not lend itself to beneficial problem solving. For me, the means by which I attempt to formulate goal-oriented battle plans generally takes the form of confetti being launched into the sky rather than anything approximating the Dewey Decimal System. In those dire times, I often attempted to overcome this clear mental malady by taking my canoe out into the darkness.

My goal, once I cleared the ruminative maze presented by the moored boats, was less geographic than conceptual: As I paddled, I let my mind drain completely down to the marrow of empty-cup nothingness. “Thought not,” I called this half-meditative state. Sometimes, it was achieved solely by via the calming quietude of the river. Other times, it was achieved by the sheer exertion required to propel a heavy, half-waterlogged, half-dry-rotted canoe through wind-whipped swells. Usually, it was a gratifying combination of the two.

This go-round, though, there was no “thought not” to be had, no matter my cadence, no matter my forcefulness, no matter the quiet. The harder I tried, the more pronounced my frustration became. I was unable to ignore that I was at the end of my tether vis-à-vis my wretched lifestyle situation. At the same time, I could not stop thinking about the circumstances surrounding the young lady who got shit upon. On the surface, it would seem like these two topics would be mutually exclusive, except, of course, they each contained the same central character: me. Pitiful, fucked-up me.

This was not the best of contemplative circumstances in which to be paddling out into water that had the ability to transform into a maelstrom without notice. I could not tell if I was paddling away from something I could not define or paddling toward something indefinable. I feared this was the mindset that causes people to convert to the lunatic theological fringe, to join up with Scientology or the Peoples Temple. Had a Hare Krishna acolyte cruised by on a Jetski or risen from the deep like a saffron-robed Neptune, bearing propaganda pamphlets instead of a trident, I might have spent the last three decades sporting a shaved pate and pestering passersby in airport concourses.

Though I am hardly an expert on the subject, I suspect the underpinnings of religious epiphanies take many forms. Perhaps a person inclined toward, or at least open to, spiritual transformation viewed a particularly stunning sunset over the Grand Canyon and came to the teary-eyed conclusion that a natural splendor of that ass-puckering magnitude could not exist without divine design. Maybe it was witnessing the birth of a child. Or maybe surviving a near-death experience, such as — as but one random example — getting attacked by a phantom shark.

It’s my guess witnessing a seagull shit on a girl’s head is one of the more rare impetuses of conversion.

That aside, my confused desperation landed me within an inch of partaking in what for me would have once been inconceivable: I started to pray. To what, I can’t specifically say. To whatever was out there trolling the airwaves for disorientation, disillusionment and despair, I guess. For what, I also can’t say. Salvation, maybe. Failing that, enlightenment. Failing that, a new canoe.

As the first tentative syllables of incohesive, ambiguous supplication started to pass my lips, I looked down and spied a response to my prayer before it was even fully uttered: In my pensive frame of mind, I had neglected the most foundational mantra of even the most modest maritime travel: be here now. Given its leaky condition, my canoe required frequent bailing, which I had let slide. Thus, I found myself mid-calf-deep in warm H2O.

Muchas gracias, celestial puppeteer!

The sodden boat was so heavy, turning it around was near-bouts impossible, so I simply turned me around, kneeled in the brine and, with purposeful exertion, pointed the stern — now the bow — back toward the marina, which was stunningly distant. Fortunately, the tide was with me and, a sweat-drenched hour later — during which time I had to mix my strokes with enthusiastic water removal — I was back among the boats. As I made my way around the dock, I almost paddled into the ass end of a 40-foot impeccably clean and tidy bright white fiberglass motor yacht. Yes, the very same vessel that bore the young lady upon whose head the seagull had shit. Between the moonlight and the faux ship lanterns scattered around the marina, I could easily make out the name of the boat:

HEREAFTER

Annapolis, Maryland.

Though, in actuality, all I could read was HEREAFT because the last two letters, large though they were, were obstructed by the flitting bare feet of none other than the world-famous shit-headed girl. Her hair was now up in a bun, and she was dressed in captivatingly short shorts and an equally captivating tight tube top.

Part Three

“I’d rather not know a lot of things.”

— Overheard in a New Mexico bar, sans discernible context

She smiled coyly at my approach.

“Strange name for a boat,” I said by way of a feigned disinterested greeting.

“She was already named when we bought her, and it’s supposed to be bad luck to change a boat’s name,” the shit-headed girl responded with the slightest hint of a distinctive Tidewater lilt. “At least that’s what my parents said. Truthfully, they’re not very original.”

“Aha. You feeling better?” I asked.

“Sorry for all the drama,” she said in a tone clearly indicating she was not the slightest bit sorry for all the drama, a tone indicating, without drama, her life force would likely dissipate.

“Well, everyone has a bad day,” I responded with a degree of false forgiveness bordering on conversational larceny.

“I’ve never been in a canoe,” she observed, deftly and casually changing the subject.

I asked, “Where are your parents?” (First things first.)

“At the marina bar. They won’t be back for a while.” Her tongue flicked and she provocatively licked, and gently bit, her lower lip. My nether regions stirred.

Awkward silences often distort the very fabric of the space/time continuum. It seemed like an eternity for a very unforeseen mental wrestling match to transpire and resolve itself within the bowels of my cranial mainframe, which had only recently been the venue of a less-lecherous train of thought. Earlier in the day, I had recoiled from this delectable morsel, despite her undeniable outward attractiveness. Hormones being hormones, though, and scruples not being scruples, I found myself weighing the potential pros and cons of continuing this discussion.

I have been blessed with superlative balance, and the canoe was designed for flatwater, so it was relatively stable, although it was still leaking like a loose cotton diaper. With confidence, I stood up, with the intention of extending a hand to the young lady, to welcome her onboard and, should she find herself able to overlook the obvious fact that, within minutes, we might sink outright, of paddling her sensual self around the harbor.

During my mom’s last years, I assume as part of an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to make amends, she told me, ever since I was old enough to don proper trousers, whenever I was agitated or nervous or confused, I would instinctively put my hands in my pockets. The one time I took a drama class in college, the professor said the same thing. Instead of reaching toward the young lady, my hands unconsciously roto-rooted their way into my pockets.

I wasn’t agitated or nervous, but I might have been a bit confused. I was perfectly confident in my ability to verbally engage members of the opposite sex, a behavioral inclination that had much to do with my long-time girlfriend, the very one for whom I had returned East, having justifiably dumped me. Still, if I possessed one trait that was able to mitigate, if not negate entirely, my perpetual desire to chase tail it took the form of my aversion to crazy women, an especial concern when one is trolling for females in the heart of Dixie, a territory thick with estrogen-enhanced madness. So, I stood there, contemplating the potential ramifications that might visit me should I proceed with my mounting carnal desires.

As my hands began to tentatively leave their cave-like resting places, the bottom fell out.

Literally.

The canoe gave up the structural ghost and, like a drive-up bank deposit canister being sucked into oblivion by a pneumatic tube, my feet broke through and I whooshed straight down. In the blink of a very flummoxed eye, the only part of my body remaining in the canoe was my head, my chin having arrested my downward plunge in such a way my jaw ached for weeks. The rest of me was beneath the canoe. My now-submerged hands were still in my now-submerged pockets. Had even one arm been outstretched, my descent would have been partially arrested and I would have merely suffered the indignity of looking like an explorer mired in waist-deep quicksand in a grainy black-and-white Tarzan movie. As it was, my feet were, improbably, thrashing underwater for the second time in less than three-hours. There was pain along my shins, ribs and shoulders, as the protruding slats of the canoe’s compromised deck had cut into those parts of my skin that contacted them on the way down. Now, there was blood in the water. And it was mine. And it was dark. And, with the incoming tide, the river was so deep I could not stand.

The young lady was surely perplexed in the extreme. One moment, there she was, sitting provocatively on the Hereafter, almost eye-to-eye with yours truly. The next instant, yours truly disappeared through a rabbit hole, as though I was the unwitting audience participant in a magician’s disappearing act. Eventually, she peered over the Hereafter’s railing. She was greeted by the sight of an apparently disembodied noodle lying disconsolately in the bottom of a boat fast filling with water.

I had removed my hands from my pockets and I was trying mightily to lift the canoe, which I was wearing more or less like a giant Tudor-era neck ruff, from my head. As I was struggling, the girl darted away, only to return with a gaff, which she courteously extended down toward my frantic face.

“Well, what the fuck am I supposed to do, grab it with my mouth?” I bellowed.

“Oh, yeah, right,” she said, tossing the ineffectual implement aside.

Her eyes narrowed and she without hesitation undertook a very poorly conceived plan-B: She nimbly lowered herself into the canoe and planted one foot on each side of my head! Why she did not too fall through the bottom I cannot say. Perhaps it was because of her slight build. Perhaps it was because I had had the misfortune of standing on the most-rotted part of the deck. Either way, her sudden presence did not aid and abet my increasingly frenetic effort to extricate myself from a situation that, given the added weight of another human being to my imminent survival equation, had become physically unachievable. The young lady opted to grab hold of my ears and begin pulling upward, as through she might raise my entire body back up from the Stygian depths through the gaping aperture in the bottom of the canoe, an absurd strategy made even more absurd by the reality that the jagged edges of the hole through which I had fallen were all oriented downward in the direction of my unceremonious submersion.

All attempts to persuade the young lady to cease and desist her fruitless, though much appreciated, effort failed, since my mouth was bobbing beneath the ever-rising waterline with disheartening frequency. Only every other syllable was comprehensible and my ill-timed vocal cadence resulted in the lady hearing only “PULL” and “HEAD” from a garbled sentence that, fully stated, was “Don’t pull my head!” Basically, I found myself engaged in an unleveraged tug of war over my own dome with a surprisingly motivated, to say nothing of impressively strong, woman.

With the water now reaching nose level, my adrenaline-based survival mechanism kicked into high gear and, with a mighty heave, I pushed upward on the bottom of the canoe, which was still bearing the weight of someone who was still tugging upward on my head. My superhuman effort bore fruit. My ears, though stretched out by several inches, slipped through the shit-headed girl’s fingers. I was free to swim from beneath the canoe.

When I surfaced nearby, my ineffectual rescuer was on her knees in what was left of my canoe, her arms reaching desperately through the hole, while sobbing, “Oh no! Please come back! PLEASE.” When she heard me gurgling my way toward the same barnacle-covered ladder I had used earlier in the day, her mandible hyper-distended, as though she was witnessing resurrection in the flesh.

I did not emerge unscathed. The sharp points of wood had cut my neck, forehead and cheeks, making it look like I had nosedived into a meat grinder. We sat on the dock as the young lady dabbed my wounds with paper towels she had retrieved from the Hereafter’s galley.

We began to chat.

Her name was June.

Her parents called her June-bug.

Her friends called her Junie.

Her enemies called her Loony Junie.

She had two older sisters, now married and moved far away, named April and May.

“Like I said, my parents aren’t very imaginative,” June said.

June’s father, was a workaholic high-and-mighty Department of Justice attorney in D.C. She rarely saw him during the workweek and, even when he was home, he paid her little heed, which she thought weird.

“The babies of the family are supposed to be doted upon,” June said. “But I was his last hope for a son. I was born a disappointment.”

Her mom, according to June, was a perpetually disoriented alcoholic accessory piece. Her dog had recently run away. She was a half-assed student who two weeks prior had graduated by the skin of her teeth from a distinguished private high school. Her only extracurricular joy came by way of ballet. Though a devoted, life-long student, she had never landed a big part.

“I am well below the cut-off point for the next level,” she sighed. “Much more talented than the average person, but much less talented than the average ballerina. I have strength and I have rhythm. According to my instructor, I just don’t have the required grace and poise. She has suggested I maybe try something less structured and less demanding, like modern dance.”

A private all-women’s college, her mother’s alma mater, loomed. She would probably end up majoring in education, just like her mom and her sisters. It was doubtful she would ever teach. “I’ll probably meet my future husband by my junior year, like my mom and my sisters. It’s all mapped out. I’ll become a perpetually disoriented alcoholic accessory piece, just like my mom and my sisters. I figure I’ve got two or three years before the downward spiral begins. I guess I should have some fun while I can.”

Our faces moved close and her hand nicked mine. “What about you? You look like someone who writes his own life story.”

It was an interesting interrogative, followed by an equally interesting declaration, since she had not yet bothered to ask my name.

As I was about to embark upon a very fictitious verbal autobiography, replete with a detailed recounting of my recent conversion to the writings of Thoreau, we heard an argument approaching. Her parents had returned. “Junebug, we’re home!” her mom slurred thunderously. After a quick hug, the kind that lingers like a low-dose jolt of electricity, I slipped into the night, abandoning my pitiful canoe to its fate.

Part Four

“There is no God, and we are his prophets.”

— Cormac McCarthy, “The Road”

When I awoke at dawn in my rundown trailer way out in the mosquito-infested fringes of this squishy-moist land, my sleeping bag was streaked red. I treated my cuts and abrasions as best I could with the last long-expired remnants of a backpacking first-aid kit that had not been replenished since I moved back East almost a year prior.

Later, there was a knock on my front door. It was my landlord who held in his hand an officious-looking document peppered with the words “whereas” and “wherefore,” which stated in no uncertain terms that my roommates and I were being evicted for a series of extra-legal transgressions we could not in good conscience deny.

On my way to work Monday morning, my battered van with dangling fenders spat a noisy billow of black smoke and died right there on the side of the highway. I had to hitchhike the rest of the way. By the time I arrived, two hours tardy, it was already stifling hot. My canoe was nowhere to be seen. I looked in every nook and cranny, under docks and behind boats, angry I had not pulled it ashore. The canoe, its structural faults notwithstanding, was one of the few things that had kept me semi-sane during the previous few months, and I had not even thanked it or said good-bye or made arrangements for a proper new life as a decorative planter. Par for my performance course.

The Hereafter was also gone, and so, I realized, was whatever slim inclination I had to give another single second’s worth of thought to the admittedly inexplicable circumstances that might cause a pile of seagull shit to land upon a girl’s head on an especially stifling mid-July Friday late afternoon. The driving force behind my de-conversion, which had made me toss and turn throughout the weekend, was the realization that, my previous perspective to the contrary, of all the people I had recently met who deserved to get their head shit upon by a seagull, June was last on the list. She seemed like she already had enough shit in her life. There were many far-more-deserving targets. Thing is, we’ve all been shit on, one way or another, to one degree or another. In the end, it doesn’t really mean a goddamned thing. As June clearly showed, a little dip in the river is all it takes to wash even the biggest, funkiest pile of shit away. At least temporarily.

“You look like you lost whatever fight you were in,” one of my co-workers said, snickering, upon viewing my lamentable state, which included much in the way of oozing scabs and yellow/blue bruises that were long to fully heal.

“You’ve got no idea,” I responded in a neutral tone.

I limped up to the topmost reaches of the marina’s highest level and looked out upon the estuary that, in a perpetual zero-sum game, brought boats here and then away. I reopened the cans I had sealed three days prior when my services were required down below. I dipped my stiff brush into the viscous crimson vat and took up my station once again, haphazardly slopping paint on surfaces so decayed, they were structurally disinclined to accept a new coat of beauty.

All around, seagulls jabbered, frolicked and lighted upon unattended shiny boat railings, only to be shooed away by well-fed owners, none of whom apparently wanted to deal with expensive brass work sullied by avian caca.

Way out on the farthest reaches of the hazy skyline, headed toward the Chesapeake Bay, I thought I made out a lone object bobbing on the waves. Though I suspect there was hopeful projection at play, I like to think it was my canoe, which, despite its terminal wounds, had found the strength and the resolve to maintain its buoyancy.

We are all vassals of the vexations and vicissitudes born by the great elemental forces that control every aspect of existence. Solar forces. Gravitational forces. Tectonic forces. Glacial. Social. Chronological. Dimensional. And, yes, maybe even spiritual. These forces are so powerful and irresistible that, most times, the best we can do is keep our heads above water and hope they conspire in their dispassionate way to take us somewhere nice. Or at least acceptable. Or tolerable. When we find ourselves dodging shit falling from the sky, making the best of our circumstances is of course an option — and maybe even an admirable option.

It all makes me want to shake my fist and spit with disgust. Then I remember that, within the very fabric of those great elemental forces, lie eddies and interstices and counter-currents as much part and parcel of the natural order as the fission burning at the heart of the Sun and causing, in a series of highly unlikely compounding component coincidences, the Earth to rotate with an axial tilt while the Moon moves above in an orbit both elliptical and inclined, consequently pushing and pulling the ocean’s waters in such an inexplicable way that we have the very tides lapping below my paint-stained perch.

It takes impeccable timing to access those eddies and interstices and counter-currents. It takes perceptiveness and intensity, maybe a bit of contrariness, and maybe even a little bit of luck to be able to pull away from the irresistible momentum born by the great elemental forces. But it can be done. It has to be done.

Inside the front door of the marina store, there was a big stack of tidal charts, necessary accouterments for coastal living. Even seasoned mariners need to refer to these charts, so they know when it’s time to stay put and when it’s time to go. Soon, the tide would be at its lowest. Then, it would predictably rise and, when it crested six some-odd hours later, there would be a tenuous balance — only for the briefest of moments — when the Earth and the Moon were perfectly aligned. The tide would then recede. Within its embrace, it bears the capacity to carry anyone willing to take a leap of faith to, well, you never really know till you get there.